Community Action History

A History of Community Action

The relative prosperity of the 1950s masked a dramatic increase in poverty among children, people living in rural America, and racial minorities. In the 1960s, the country boiled with urban riots, the Vietnam War, assassinations, civil rights conflict, persistent poverty, and a Baby Boomer generation agitating for peace, justice, and rock and roll.

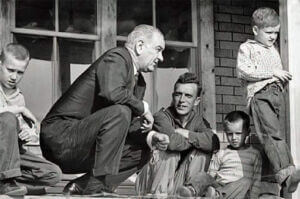

The tumult spawned President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Out of that arose Community Action Agencies, which remain a major force in childhood education, helping seniors and the homeless, assisting families to buy and fix up homes, and improve their personal finances.

Community Action was first modeled after programs addressing urban renewal and youth unemployment, and which linked local officials, service agencies, and neighborhoods. In 1961 President John F. Kennedy launched the “New Frontier” in New York City with the Mobilization for Youth (MFY). Backed by the city and the Ford Foundation, MFY organized neighborhood councils of local officials, service providers, and neighbors to combat juvenile delinquency. Another Ford Foundation-funded project in New Haven, Connecticut, recruited various community sectors to help low-income people.

The idea was expanded to address general poverty. After Kennedy’s assassination, President Johnson carried on the anti-poverty vision with Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 (EOA). The legislation created the federal Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), first led by Sargent Shriver and placed under the President’s direct control.

Community Action Agencies were created to fight poverty at the local level. The OEO and Community Action network would launch iconic names in U.S. human services: Neighborhood Youth Corps, Head Start, VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), and the Job Corps.

Community Action programs survived federal government attempts to cut funding and urban mayors who viewed the agencies’ advocacy for the poor as a rival for solving problems and in building a relationship directly with citizens. Community Action programs were designed to attack root causes of poverty and create opportunity; they also were aimed to directly intervene in the unique problems of local communities with such basic emergency needs as paying heating bills or providing meals. Community Action Agencies have evolved from neighborhood-based organizations that identified barriers in their communities that prevented local citizens from climbing out of poverty, to larger regional programs that serve at least one county or larger. The Community Action model is an immediate local response that focuses on problem solving. The mission is larger than serving the poor – it is to change communities for the better in lasting ways.

Unlike specific government programs, the Community Action agencies tailor assistance for residents to solve local needs driven by a community needs assessment process and stakeholder engagement. For example, farming communities might need help forming cooperatives. Urban cities might need more job training or after school programs for low-income children. Uninsured families may need a local health clinic in an underserved neighborhood, or a rural community might need a doctor.

Sometimes Community Action is a convener or planner. Sometimes it delivers direct services to alleviate the causes or conditions of poverty. The agencies are controlled by local boards with no prescribed programs, except the ones the community feels it needs and wants to serve its residents.

“There’s a saying, that, if you’ve seen one community action agency you’ve seen one community action agency,” said Ron Borngesser, Former CEO of the Oakland Livingston Human Services Agency. “They’re all different in how they serve the community.”

One example of changing needs was the surge of home foreclosures during the severe recession that began in 2008. Community Action Agencies were pressed into service to help homeowners avert foreclosures or find other housing. The demand for help was overwhelming, Borngesser said, even in relatively affluent Oakland County.

Originally, funding for Community Action Agencies came directly through the federal OEO. Across the U.S., Community Action Agencies opened neighborhood centers in low-income areas to identify and help those who needed it.

In 1967, Congress passed what was known as the Green Amendment, which required that CAAs be designated by local elected officials, such as mayors. In some large cities, CAAs were taken over by mayors and turned into public agencies. In Michigan, some of these programs evolved into county-based Community Action Agencies, which are part of local governments, while the remaining agencies operate as private, nonprofit agencies.

Another congressional action, the Quie Amendment, required at least one-third of CAA boards to be elected officials; other board members represented low-income people and the private sector. The inclusion of local officials is one reason Community Action has survived and maintained its standing in Congress, says John Stephenson, former executive director of the Northwest Michigan Community Action Agency, which serves 10 counties in northwest lower Michigan. He says many members of Congress have either served on Community Action boards or know people who have.

“It’s a testament to bi-partisan support,” Stephenson explains. “There have been presidents who wanted to de-fund Community Action, but Congress has not let it go. We’ve done a pretty good job nationally of keeping Congress aware of what Community Action is doing in their districts and recognized as a value.”

By 1968, there were 1,600 local CAAs covering more than two-thirds of the nation’s 3,300 counties. Today, 1,000 CAAs remain, some having merged, but now covering 99% of counties. Recruiting elected leaders, residents who were eligible for programs and services, and other community leaders to serve on CAA boards proved to be positive, as it bonded the power structures of local politics, economies, and activists to forge policies and programs that helped low-income people.

In 1973, the existence of CAAs was threatened under President Richard Nixon, who sought to eliminate funding for the OEO’s Community Action Program. A federal lawsuit eventually halted Nixon’s attempt to dismantle the agency, after he had successfully transferred large OEO programs to other federal departments.

The federal leadership and administration for CAAs changed in 1974, under President Gerald Ford. The OEO was replaced by the Community Services Administration (CSA). The CSA continued to fund Community Action Agencies for such self-help projects as gardening, solar greenhouses, and housing rehabilitation. Home weatherization programs began in the 1970s.

Later, under President Ronald Reagan, funding for CAAs was switched from direct CSA appropriations to a program of block grants, which gave states more control of the money. Congress refused to eliminate CAA funds altogether. However, some activities were prohibited, such as registering people to vote. The Community Service Block Grant (CSBG) is the hallmark of community action programs.

In 2003, Michigan Public Act 123 created the Bureau of Community Action and Economic Opportunity and the Commission on Community Action and Economic Opportunity as the administrators of federal funds used by CAAs to combat poverty. The bureau, which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services, distributes over $23 million to CAAs from the federal Community Services Block Grant, which helps leverage over $438 million in funds from private and local government sources. Some programs, such as Head Start and the Weatherization Assistance Program, receive separate federal funds.

“Over the years, Community Action has improved its effectiveness by helping low-income families with long-range needs,” said John Stephenson of the Northwest Michigan Community Action Agency. “Paying a monthly home heating bill might come with helping a family improve its budgeting and a financial plan to avoid future crises.”

“There’s recognition across the country that we need to better demonstrate successful outcomes, rather than just delivering services,” Stephenson said. The use of comprehensive national organizational standards and reporting outcomes based on both local and national goals continue to make Community Action unique and effective.

Today, Community Action Agencies in Michigan excel in developing affordable housing, distributing food, weatherizing homes, assisting families and veterans with emergency needs, helping with financial literacy/budgeting, preparing people to return to work, and offering a wide array of services for vulnerable seniors and early childhood programs for children and their parents. Some agencies also work specifically with veterans, migrants, and the disabled. A few even run transit agencies in their areas. CAAs continue to play an important, leading role in Michigan’s economy and social service network.